He is forty years old. This alone I find incredible. With his withered arms he brings out some papers from within his shirt, among them is an address book. He has friends everywhere. He corresponds with Europe and America. For some months he lived with some Germans in their rented rooms until their visas expired. There is an exchange of letters also with a wheelchair firm in Calcutta and a scheme for sponsoring the construction of a special device to wheel him around. From this almost nonexistent being on a pavement in Pondicherry, a field of consciousness reaches out around the globe. As far as I know he is not a great painter or poet or musician, though it would be wonderful if he were, but his accomplishment is much greater than that. Against all the odds he has refused to disappear.

In the above passage, it is 1973. Ted Simon circumnavigates the globe on his Triumph motorcycle. In India, he confronts a disfigured beggar. The beggar shares his extraordinary story and explains to Simon how his marginal, stationary existence has allowed him to meet passersby from all over the world, producing an abundance of worldwide correspondence between the beggar and strangers willing to trust him.

Simon uses the phrase 'field of consciousness' to describe the effect emanating from the hands of this mendicant -someone whom the cruel might deem a useless nuisance- through the conveyance of written letters toward the greater world. The correspondence provides a rich awareness for both sender and receiver; the effect is edifying for all.

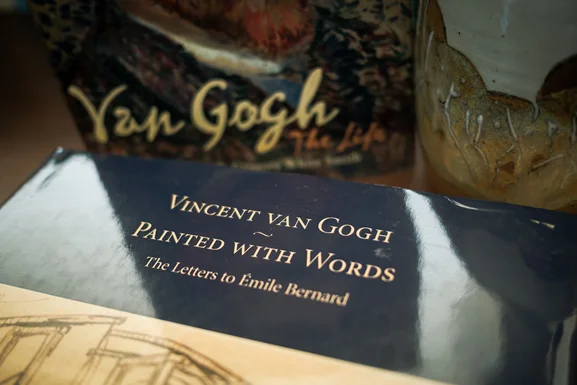

Several volumes of letters grace my library shelves: the letters of William Styron, Elizabeth Bishop, Gustave Flaubert, Wallace Stegner, T.S. Eliot, Flannery O’Connor, the collected correspondence between Herman Hesse and Thomas Mann; Ralph Ellison and Albert Murray; James Salter and Robert Phelps, the staggering letters of Rilke (Letters to Merline, Letters to a Young Poet); and reaching deep into the mailbag of antiquity: Seneca's eponymous Letters from a Stoic.

The record of events, of what men have done, is relatively rich and informing. But a record of the state of mind that conditioned those events, a record that might enable us to analyze the complex instincts and emotions that lie behind the avowed purpose and the formulated principles of action - such a record is largely wanting. What one requires for such investigation are the more personal writings - memoirs, and, above all, letters - in which individuals consciously or unconsciously reveal the hidden spring of conduct. (1)

By now we know: the art of letter writing is forever lost. At best, our cursory email correspondence carves an ephemeral trail, our words (therefore our stories, our experiences, our lives) 'writ in water.'

The collected letters that remain in print for us today emanate the same field of consciousness that exude from that crippled beggar in India. We feel "the complex instincts and emotions." Remnants of the authors' spirits hallow the pages. I can drift in and out of this correspondence as one can a conversation with friends, like walking through a broad field where wildflowers of reflections and introspection offer a fragrance for the lonely traveler.

César Aira’s An Episode in the Life of a Landscape Painter is one of three small thin volumes I currently carry in my camera bag. It's a contextual read, a book best savored in places that nurture a creative mindset (within the strictures of meditative activities, like hiking or canoeing or flaneuring with camera).

In Episode, the protagonist (Rugendas) lay horribly disfigured, the result of a freak accident. As he lay convalescing, he turned his thoughts toward letter writing, an activity he pursued his entire life. But letter writing became more than correspondence, it was now a forewarning to loved ones of his tragic deformity (foreshadowing his arrival in person) and more importantly, a mode of emotional disentanglement:

But he also needed to clarify things for himself and come to terms with the gravity of his situation, and the only means of doing so at his disposal was the familiar practice of letter writing … As if he had been aware of it from the start, Rugendas had prudently built up a range of correspondents scatter around the globe. So now he resumed the task of writing to other addresses; among his interlocutors he counted physiognomic painters and naturalists, rangers, farmers, journalists, housewives, rich collectors, ascetics, and even national heroes. Each set the tone for a different version, but all the versions were his.

Perhaps Rugendas found, not merely a voice for expressing his condition, but also the silent, profound bedrock of unseen supporters, like the beggar in India whose friends' emotional, physical, and psychical substructure aided him in his fragile condition. Perhaps it is this same foundation that the German writer Herman Hesse consciously built upon, writing over 35,000 letters in his lifetime. Or, as Seneca stated over two-thousand years ago, a substrate emanating a palpable presence of the real:

Thank you for writing so often. By doing so you give me a glimpse of yourself in only the way you can. I never get a letter from you without instantly feeling we're together. If pictures of absent friends are a source of pleasure to us, refreshing the memory and relieving the sense of void with a solace however insubstantial and unreal, how much more so are letters, which carry marks and signs of the absent friend that are real. For the handwriting of a friend affords us what is so delightful about seeing him again, the sense of recognition.

I am reminded of a passage by Stephen Dunn:

You who are one of them, say that I loved

my companions most of all.

In all sincerity, say that they provided

a better way to be alone.

Emile Bernard, speaking of the many illuminating letters exchanged between himself and Van Gogh, claimed they were the 'bond that joins us together; they enabled us to love each other, to know each other ... only to me did he entirely let himself go.' Alexandra Styron, daughter of famed writer William Styron, speaking of the relationship between her father and writer Peter Matthiessen, 'Perhaps nothing was as crucial to the longevity of their fellowship as the great and lost art of letter writing.'

To be alone with friends is companionship that retains a redolence even in absence. Email can rarely mean for us what a sheaf of letters and aromatic mixture of ink and sheared wood can, email can never possess the 'secret soul of things,' email cannot transmute thoughts like the curvature of handwritten script, the fade of ink, the impress of emotion. Wendell Berry wrote, 'imagination thrives on contact, on tangible connection.' Because we have lost the tactile carrier of our deepest sentiments, because its physicality can no longer enchant us, we have lost entire landscapes, vistas, 'vast structures of recollection.'

Letter writing is probably the most beautiful manifestation in human relations, in fact, it is its finest residue.

- John Graham, 1958, from More Than Words

(1) Carl Becker, from The World's Greatest Letters

(2) Stephen Dunn, “A Postmortem Guide” in Different Hours