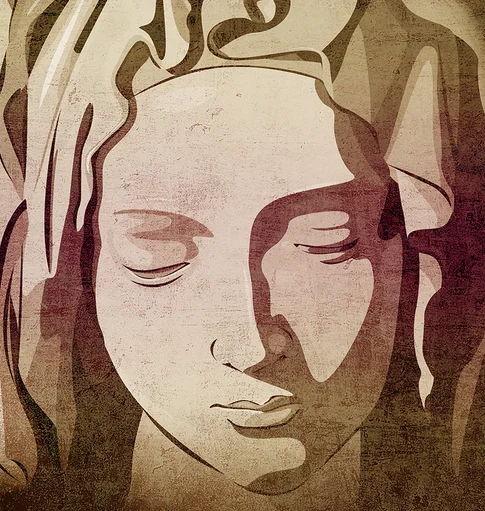

Pieta (A Ghazal)

Cradled in his mother's lap he lies, a thousand times.His death, not just once, he has died a thousand times.

Coniferous marvel, yield your miracle, but your evergreen leaves I despise a thousand times.

The quiver shakes: the last red arrow sails the sky, the fawn leaps in futile flight a thousand times.

The Christ is thirty-three; you are forever three. Defy the threat of hope's demise, a thousand times.

The horizon's brim rests regal, sated with wonder. My heartbeat I trivialize a thousand times.

Insulate yourself from life's grim reality, but mute your attempt to sermonize, a thousand times.

Alone in deaths wake, from cavernous darkness she yearns and bleeds her tremulous sighs a thousand times.

Though curves and kerns mete out daily sustenance the letters dance in veiled disguise a thousand times.

Steal her breath horrid black thief but she'll caress, sequestered in her mind, his smile, a thousand times.

"No survivors but we must deploy the life raft", echoes the doctor's reply a thousand times.

The artist's hand now haunts his one pieta, prized; you, I'll attempt to eulogize, ten thousand times.

About this poem:

This poem is a Ghazal, one of the oldest forms of poetry going back to seventh-century Arabia.

Ghazals, according to Elizabeth Gray, are often "puzzling to the Westerner who approaches them for the first time...The poems do not seem to go anywhere: there is ... no ultimate resolution or answer. [The couplets] seem unrelated to one another. And everything seems ambiguous: Is the poet talking to the one he loves? Or is he approaching a patron? Or is this a nugget of wisdom at the disciple who seeks union with God? If the poet is talking about his beloved, is the beloved man or woman? Is it actually the poet talking?"

"The Ghazal is made up of couplets, each autonomous, thematically and emotionally complete in itself...There is, underlying a Ghazal, a profound and complex cultural unity, built on association and memory and expectation, as well as implicit recognition of the human personality and its infinite variety....One should at any time be able to pluck a couplet like a stone from a necklace and it should continue to shine in that vivid isolation, though it would have a different luster among and with the other stones." - Agha Shahid Ali, Ravishing Disunities

Agha Shadid Ali captured the emotion of a ghazal with this definition: "It is the cry of a gazelle when it is cornered in a hunt and knows it will die".

For me, the Ghazal represented a form to (once again) reflect upon my son's death (and, in doing so, register a protest -in places- to not merely reflect upon death, but to also reflect upon his life). Grief is irrational. There is no appropriate grieving process. There is no requisite time period for grieving nor closure (there is no conclusion; grief pervades). The ghazal form with its ambiguities, its dissonance, its (seemingly) incoherent pattern and meandering, mirrors the irrationality of grief. Grief is parceled out in heaves of despair but also in tiny moments, moments that continue throughout (I can only surmise at this point) ones entire life.

Though the poem is titled, "Pieta", it is not about Christ, it is about the countless moments I have in my memory (the "thousand times") where I witnessed my wife cradling our broken son through his long illness as well as the image of her cradling him in his death (like the Christ in Michaelangelo's Pieta). Grief is the "thousand times" I've thought of him. The "thousand times" I've envied an evergreen tree because it lives and leaves in all seasons. The thousand times I'm haunted by his painful moments (and yet, our little fawn "leaps his futile leaps"). The thousand times I've despaired of hope. The thousand sighs my wife has sighed. The thousand times I've hid behind these letters and books of mine, "veiled disguises". The thousand times I've heard the echoes of the doctor's words, despite the knowledge that the odds for survival were virtually nonexistent. Every couplet above resonates with one of these moments, these "thousand times". Michaelangelo signed only one work, his Pieta, and, true to the form of the Ghazal, the author "signs" his name in the last line. My signature is one of a commitment to continue to eulogize my son, in words, in poems, in thought, and in deed, "ten thousand times".

(A technical definition of the Ghazal is provided by The Academy of American Poets: "The ghazal is composed of a minimum of five couplets—and typically no more than fifteen—that are structurally, thematically, and emotionally autonomous. Each line of the poem must be of the same length, though meter is not imposed in English. The first couplet introduces a scheme, made up of a rhyme followed by a refrain. Subsequent couplets pick up the same scheme in the second line only, repeating the refrain and rhyming the second line with both lines of the first stanza. The final couplet usually includes the poet's signature, referring to the author in the first or third person, and frequently including the poet's own name or a derivation of its meaning.")

Image credit: Omar Palma